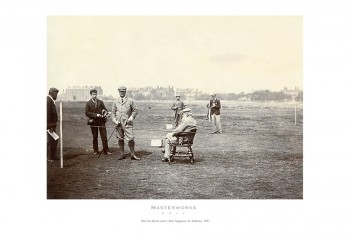

Photography and the modern game of golf developed around the same time. Coincidence? Probably, but it was a fortuitous coincidence since we’ve been left with at least some photographic history of those early years.

It’s likely that the largest and highest-quality collection of early golf photography is in the hands of Howard Schickler of Sarasota, Fla., who has been slowly building the collection for the past ten years.

An avid golfer since he was a teenager in New York City and later a collector and exhibitor of historical fine art photography, the two avocations will culminate in the launch of a website dedicated to golf’s history and the sale of museum-quality prints. The website’s launch is set to coincide with the British Open in late July.

Currently, you can see part of the collection at www.masterworksofgolf.com. We’ll update you here at the LexJet Blog when the new site, which will have a slightly different URL, is up and running.

“I started buying historical golf photography with a museum curator’s eye of building a collection that was museum quality and meaningful. What I decided to do from the beginning was only collect photos related to the major champions of golf. I also added golf courses of extraordinary quality by great photographers,” says Schickler. “I’m always in pursuit of the very earliest pieces which date mostly from the 1850s, but they’re extremely difficult to find. I’m able to count on one hand how many photos I have from the 1850s.”

Schickler was recently invited to exhibit some of his collection at a festival at St. Andrews in Scotland, the birthplace of modern golf. He chose 13 images to print for the festival, which were exhibited in two different venues. Schickler brought 26 prints (13 for each venue) to the festival. The images were printed by Schickler and his son, who’s studying digital photography at the Ringling College of Art and Design, at 13″ x 19″ on LexJet Sunset Hot Press Rag on Schickler’s Canon iPF8300.

Schickler was recently invited to exhibit some of his collection at a festival at St. Andrews in Scotland, the birthplace of modern golf. He chose 13 images to print for the festival, which were exhibited in two different venues. Schickler brought 26 prints (13 for each venue) to the festival. The images were printed by Schickler and his son, who’s studying digital photography at the Ringling College of Art and Design, at 13″ x 19″ on LexJet Sunset Hot Press Rag on Schickler’s Canon iPF8300.

“We originally tried five different papers, all of which we had experience with before. We weren’t sure if we wanted to go with fine art paper, fiber paper or a matte or gloss finish, so we would take one image and print it on the five different papers,” explains Schickler. “We found we were getting the best results from Sunset Hot Press Rag and Sunset Fibre Matte. We chose Hot Press Rag as our main paper because it really brings out the details of the images and provides the same feel as if they were printed in the 19th Century.”

The goal of each print is to stay as true to the original image as possible. Very little is done to the images, other than cleaning up a blemish here and there.

“For us, the important thing was to bring out the exact tones of the originals, which have some sort of sepia tone to various degrees,” says Schickler. “The new printers are great because they make it a lot easier to be faithful to the original tone of the image.”

Schickler left goodwill behind him after the event at St. Andrews, donating the prints to the festival organizers, all the while building relationships with venerable St. Andrews institutions, such as St. Andrews University, which houses more than 700,000 photographs in its library, many of which are from the early development of photography and modern golf.

The collection has been the proverbial (but literal) labor of love, and the website being developed right now will reflect that. In addition to an eCommerce component, which will feature a portfolio of about 60 historical images from a collection of over 1,000, there will be blogs that focus on blending historical and contemporary golf (golf fashion then and now, golf courses then and now, and so forth), and a documentary video section.

“We plan to produce 18-24 video vignettes. Each one will tell the story of great golfer from the 1850s to the 1930s. Collectively, the videos will become an important documentary film on the history of golf, which has never been done before. And, we’ll go beyond Scottish golf to ladies golf in the UK and U.S., and American golf, which post-dates Scottish and UK golf by about 40 years,” explains Schickler. “We’re also planning to create an iPhone app that reproduces a historical golf timeline with content links to images and videos from our collection. I want the site to be an aggregation of interesting, high-quality, intellectually stimulating information about golf and its history.”